Touching Time

On rocks and ruptures, and the geology of the heart

Down at Siccar Point, July 2025

James and James and John row east along the coast from Dunglass Burn to Siccar Point. They anchor where the rocks are washed bare by the wind and waves - for to view the old stone

It’s hard to feel significant when you rest upon a 65-million-year gap in geological time. At the headland of Siccar Point in the Scottish Borders, where the Forth estuary meets the North Sea, I’m caught by my, our human smallness.

To ‘mak siccar’ in Scots is ‘to make sure’, from the same Latinate root as ‘secure’. Yet there’s no sense at all, in this place, of freedom from danger or doubt, neither in the rugged physical matter of the crags nor in what this outcrop has come to symbolise in the history of scientific thinking about planetary time, and our human place within it.

Siccar Point minus small human

Back in 1788, John Playfair, then Professor of Mathematics at the University of Edinburgh, was similarly humbled, on landing at the promontory with his friends and colleagues, James Hutton and Sir James Hall. Hall, a geophysicist, and estate owner at nearby Dunglass, supplied a wee boat. Geologist, farmer and polymath, Hutton supplied the intellectual provocation: to find material evidence for his theory of uniformity i.e. that the forces which shaped Earth’s geological past were the same as those visibly shaping it still - erosion, deposition and uplift.

This sounds unremarkable now, but in its day it radically shifted scientific understanding about the age and nature of our planet.

Sharp grey ribs of rock rise up through sedimented bands of red sand, a lost seabed, lifted to the stars - so long, long gone.

It’s low tide on a July morning, the water gentle, the sky cloudless, the rock warm. House martins skim along the cliffs, and the odd gannet from the vast colony at Bass Rock, hurtles into the sea in hopes of a catch.

Siccar Point from above

I’ve looked down to Siccar Point many times before in all kinds of weather, but this is the first that I’ve scrambled down the steep bank to the water’s edge. This rugged outcrop, between the harbour towns of Dunbar and Eyemouth on Scotland’s south-east coast, is the foremost site of what’s known as Hutton’s Unconformity, a visible juncture of two different kinds of rock, from non-sequential epochs of Earth’s geological history.

Here it manifests as near vertical greywacke, a dark hardy sandstone, formed 440 million years ago in the early Silurian age, protruding through gently sloping layers of softer Old Red Sandstone of the late Devonian age, 375 million years ago. Between the older grey stone and the younger red is what’s known as a hiatus, a gap in the geological record of incremental, chronological deposition, which James Hutton dubbed an ‘unconformity’. He likened it to a missing chapter from “the annals of the earth”.

“walls and bones and oceans - the Earth is never still” (see below) - stone dyke by Siccar Point

The idea of lost pages, or an absence in an archive, is something I’ve been mulling over a lot since the recent end of a long term relationship. If it were a solution to an equation in a High School mathematics paper, I might observe, with soreness, but without judgement, that this ending hadn’t shown all of its workings. And so, the angular tilt of ruptured rock, the vast temporal gulf between one side-by-side strata and another, becomes a metaphor for an emotional landscape.

Tell this time to the ether Tell this to the ones who count the hours

Scoring the horizon, 30 kilometres into the North Sea, is an early chapter of a new human story, perhaps - the Neart na Gaoithe (Strength of the Wind), an offshore turbine array, which sends its energy to the national grid via a cable at Thorntonloch beach, just below Torness Nuclear Power Station. The latter’s blank modernist façade, due for closure in five years, is clearly visible from Siccar Point, nestled between the 350-million-year-old volcanic plugs of North Berwick Law and Bass Rock, and the serpentine, post-apocalyptic movie architecture of The Tarmac Cement Works at Dunbar. The cement plant, situated as it is beside an abundant supply of limestone, essential for its production, is Scotland’s fifth largest carbon polluter. The radioactive waste produced at Torness won’t degrade for around another five hundred human generations.

Torness Power Station, East Lothian

Closer to shore, there’s a lobster boat, pots marked with colourful buoys. And in the mouth of the Forth, several huge container ships laden with oil - the Rhogas from Norway, the Danish-registered Sword - wait for upstream entry to the Port of Grangemouth. The oil, of course, was formed on the seabed from the anaerobic decay of plankton and algae, some two hundred million years ago, during the era of the dinosaurs.

It’s hard to imagine now, but the older greywacke at Siccar Point was once marine sediment too, in the vast Iapetus Ocean, which divided what’s now Scotland from England, or more precisely, the ancient paleo-continents of Laurentia and Avalonia. This sludgy matter lithified over thousands, millions of years, before being compressed, folded and tilted upwards by immense tectonic pressure as the ocean closed and the continental masses collided. Its exposed, upper edges eroded away and ultimately disappeared from the visible rock record.

I’ve felt in recent weeks as if I’ve been disappeared too. And into the weirdness of it, I’ve reached constantly for geological imagery. When did the everyday weathering of a close relationship become irreparable erosion? How much silt and sediment had deposited itself unseen? How much was there, clogging things up, before it even began? And what tectonic forces - out there, in here - were and are simply too much for any two humans to reasonably withstand?

I’ve found a kind of comfort and dignity in stripping away the immediate questions of agency that buffeted me in the first few weeks - who did, or did not, do this or that? who left or was left behind? Viewing the ending instead as a thing that has happened, an event in the annals, doesn’t make it less sad. It does strip away a sense of wounded injustice that’s not truthful in the circumstances. And that’s a kindness, I hope.

Left to Right: North Berwick Law, Tarmac Cement Works, Torness Power Station, Bass Rock

The three men find no trace of a beginning, no prospect of an end. Deep and deeper, it lies beyond their giddy measure - in the old sandstone.

Back in 1788, when James Hutton, Sir James Hall and John Playfair landed by boat at Siccar Point, they knew they were encountering something transformative. Playfair wrote later about Hutton’s animated excitement, dancing on the sea’s edge, and of his own awe:

“What clearer evidence could we have had of the different formation of these rocks, and of the long interval which separated their formation, had we actually seen them emerging from the bosom of the deep? The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time …”

from John Playfair’s ‘Biographical Account of the Late Dr. James Hutton, F.R.S., Edinburgh’ (1805)

It's a lingering, poetic image - the abyss of time. And indeed, it was the younger Playfair’s accessible writing about, and championing of Hutton and his theories, rather than the elder’s impenetrable writing about his own work that did most to secure Hutton’s stature in the intellectual firmament of contemporary geology, as the so-called ‘founding father’ of modern scientific notions of Deep Time.

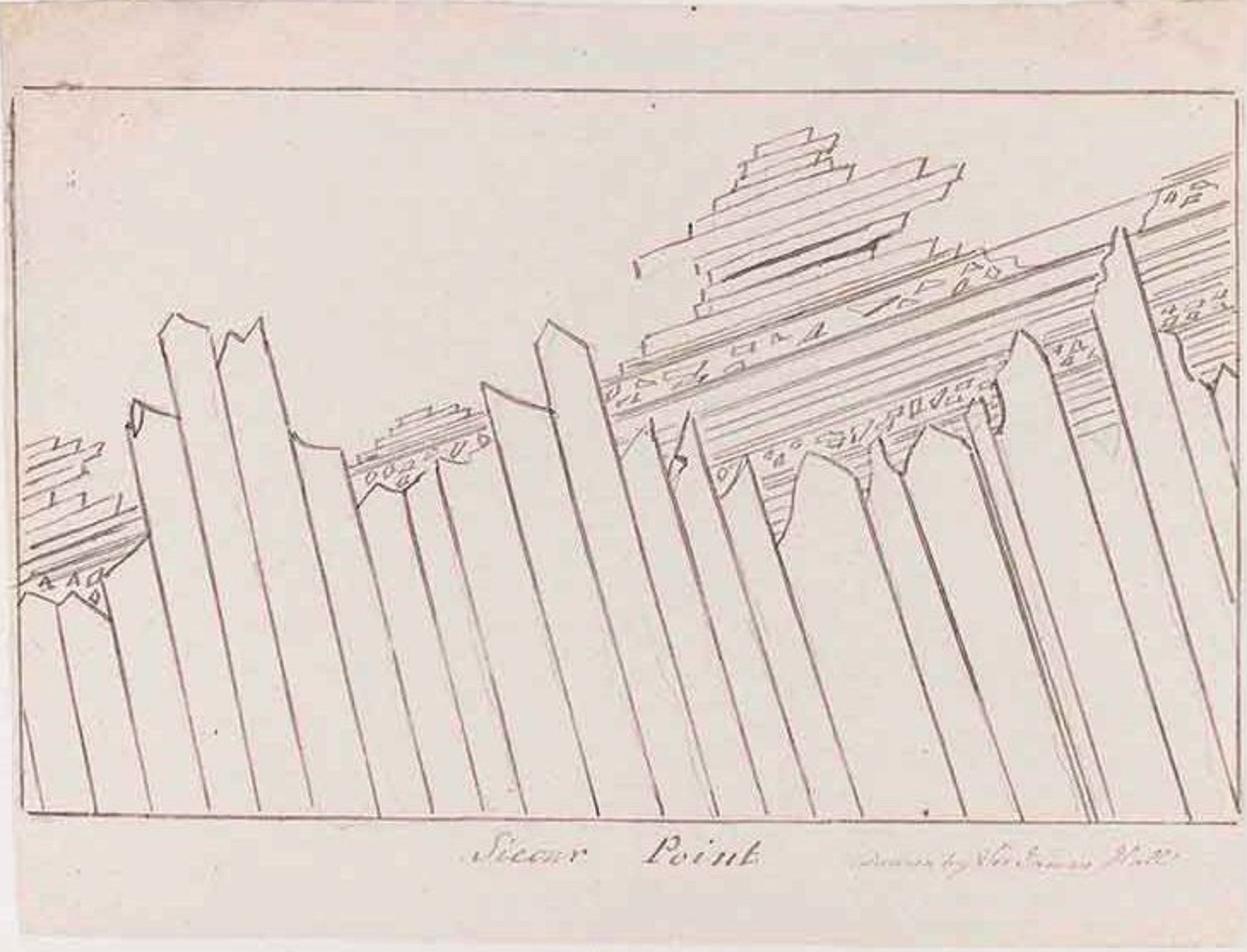

John Playfair’s sketch of the Unconformity at Siccar Point (1788)

On a day as still and glassy as this July morning, it’s hard to conceive of this landscape as volatile. Less so, on the increasing number of days that wash parts of this fragile coastline into the sea. Eleven miles north at Dunbar, following successive storms in 2014, the East beach was almost entirely eroded away and hasn’t attracted enough sediment since to reform. A chunk of the John Muir Way, a path from west to east central Scotland, named in honour of the Dunbar-born conservationist who later founded the US system of National Parks, has also fallen away. Flood projections for 2050 show the East Lothian edges of Belhaven, Tyninghame and much of Musselburgh under water.

We are not ready for this.

The surface of this land is made by Nature to decay dust cleaves to dust and then it’s blown away - by the long, long gone

Tell this time to the ether Tell this time to the ones who count the hours Tell this time to the water

I’ve been depositing my own sorrow and bewilderment into the North Sea . I walk. I ease myself into the tide. I listen. And I feel the sharp edges of my own existence briefly, incrementally softened and diminished. It helps me to sit with gigantic forces.

The Meeting of Robert Burns and Walter Scott at Sciennes Hill House by Charles Martin Hardie (Abbotsford House Collections)

There’s a fascinating 19th century engraving at Abbotsford House in the Borders, the historic home of Sir Walter Scott. Titled The Meeting of Robert Burns and Walter Scott at Sciennes Hill House, it depicts an occasion in 1787 that predates the birth of the artist, Charles Martin Hardie (1858-1916). At the fireside of his own home sits an elderly Adam Ferguson, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. The two figures standing in the foreground are Robert Burns and a teenage Walter Scott. This was the only time the two writers ever met, and by Scott’s later recollection, it was a transformative encounter for him.

What’s equally curious though are the others remembered in this Enlightenment era scene. They include: economist Adam Smith, by then famed for his An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, widely regarded as the underpinning of contemporary capitalism; Professor of Medicine and Chemistry Joseph Black, who first isolated carbon dioxide (which he called ‘fixed air’ at the time); and James Hutton, whose ideas on geological time were not yet published but already circulating in the company of his intellectual peers, following presentation to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1785.

Hutton and Burns met just this once. But I’m not the first to wonder1 whether Burns is alluding to Hutton’s thinking in his iconic love song, My Love’s Like a Red, Red Rose:

Til a’ the seas gang dry, my dear and the rocks melt wi’ the sun I will luve the still, my dear while the sands o’ life shall run.

Ach, don’t most of us wish for a love like this, something lasting? Something ‘siccar’.

I still do.

For now, though, I’ll keep turning to walking and water, wind and rocks, writing - and time, time, time.

Only one thing is sure: everything dissolves and disappears. Tears and diatoms, walls and bones and oceans - the Earth is never still, it's never still - even rocks melt in the sun. Tell this time to the ether Tell this time to the ones who’re still to come LISTEN to the musical piece Siccar Point, co-written with Dave Milligan for our 2021 album Still As Your Sleeping (Hudson Records, 2021): Siccar Point

NOTE: My writing here forms part of my activity as 2025’s Dr Gavin Wallace Fellow, funded by Creative Scotland and supported by host organisation the Fruitmarket within their programme Attached to Land: Mutual Accountability Within Environmental Permacrisis. @fruitmarketgallery @creativescots

I wanted to send you this, for a sore heart.

Your music has helped my heart be more 'loamy' on many occasions. Thank You. May healing come for you in its own way and time.

Self Compassion ~ Rosemary Wahtola Trommer

It’s like the scent of rain

after a month of drought—

the way it rises up and fills the lungs

quiets the body

and softens the mind—

that’s what it’s like

when, after grasping

and spinning and reaching

and clenching, at last,

exhausted with my own fear,

I lay my hand on my own heart

and see through my thoughts

and practice loving

what is here beneath my palm:

this frightened woman

and the life that lives through her—

not a single promise I will be safe,

but when I press my open hand

into the beat of my anxious heart

what was dry becomes loamy,

what was cracked becomes rich,

and a faint sweetness

tendrils through me like incense,

soothing as a lullaby

only the self can sing.

Fine and stimulating writing, thanks! Looking forward to seeing you at The Queen's Hall next month.